A Coaching Approach to Succeeding at What You Want

Most of us set goals for our professional and personal lives throughout the year. It is the way we grow our practices and ourselves. Most of us succeed at reaching some, or even most of our goals. Some of us are better at that than others. Wouldn’t everyone like to be successful all of the time? While 100% success is not likely, there is much we can do to improve our likelihood of success.

In my work as a career and life coach for physicians, I am often engaged with clients in defining appropriate goals for their future. Sometimes these goals are directed to aspects of their professional career and practice, and sometimes to aspects of their personal life. I’d like to share with you a coach’s experience and perspective about the process of converting goals into action. In the end, it is specific action steps and accountability which lead people successfully to their goals and their dreams.

We have all had the experience of setting New Year’s resolutions for ourselves. You have done it; I have done it. Too often, those well-intended New Year’s resolutions never became reality. We struggled with them for a while, or forgot about them until the next New Year’s rolled around. Even though we fully intend to do what we resolve on January 1 to accomplish, we are often unsuccessful because we did not convert our intention into action.

Goal setting is, after all, writing down what we intend to do. However, no matter how serious and motivated we are to do something, we must shift from intention to action in order to succeed. That is where we often encounter difficulty. I call it, “TROUBLE AT THE BORDER“, the border between intention and action. (Trouble at the border is a phrase I remember from watching The Cisco Kid serials at the movies every Saturday afternoon as a kid.)

Trouble at the border may take on a number of different appearances. It is typically related to either internal or external factors. We may encounter an inner voice in our heads saying things like, “You don’t deserve this”, or “This will require too much of an effort”, or “I can’t afford the time to do this”, or “My spouse will never approve of me doing this”, or “I’m not good enough at this to get it done”. Sound familiar? The end result of this form of self-defeating thinking is that we do not reach our goal. It may even keep us from trying! This is often referred to as Inner resistance. Whether these voices in our head are accurate or not is not the issue. What is important is that the net effect of the voices, without external support, is to cause us to self-sabotage. Internal resistance prevents us from success, even when we have all of the resources necessary for success!

Alternatively, trouble at the border may arise from factors external to us, and act as obstacles to success. Such external factors may take many forms, including financial restrictions, lack of support or opportunity from outside our immediate resources, physical restrictions which prevent us from accomplishing certain physical goals, or too little time because of a work schedule created by others. Unlike internal resistance, we may have no direct control over external resistance factors.

Working with a career / life coach can help you overcome both internal and external sources of resistance. Internal sources of resistance become less powerful once you learn to verbalize what the internal voice(s) are saying. You can then use logic, your personal skills and abilities, and the reality of your own adult experience to put those voices to rest.

As an example of working with internal resistance, a client of mine, a fellow in internal medicine at a Middle West teaching hospital, was plagued with low self-esteem. She wanted a certain prestigious research fellowship but was convinced she would never be accepted. She wasn’t even willing to apply. (The internal voices said, “you are not smart enough; you do not deserve it; you haven’t worked hard enough; and other things.) Working together on the internal resistance, her self-esteem improved. She realized that her own over-developed inner critic was severely judgmental, and did not match the way others saw her or her own record of success. She applied to the NIH for the coveted research fellowship, and was accepted for one of only three slots available. She starts July 1. So much for her low self-esteem.

Overcoming external resistance factors is more difficult, but usually possible. Successful coaching strategies include engaging your creative problem-solving skills, asking for help, making better use of resources available from friends and family, expanding personal financial resources when necessary, and obtaining new learning or training.

An example: A depressed and overly stressed pediatrician sought my help to re-engineer his practice to reduce his stress. He was seriously considering leaving practice altogether. During coaching, he revealed that he had always wanted to work in TV and radio, not medicine, but had been coerced into medicine by his father. He saw no workable solution to get himself involved in the field of his dreams. Using creative problem solving, asking for help from his local radio station manager, taking a few courses in communications, volunteering time at his local TV and radio stations, and with the financial support of his working partner, three years later he now is a respected commentator on his local TV station, he has produced three health-related programs for NPR radio, has reduced his clinical practice by 25% to accommodate his new career, and he can’t wait to get out of bed every morning to enjoy either his practice or his new media career.

Physicians often struggle with the challenges of external resistance because we find it difficult to ask for help, to accept help when it is offered by others, and we prefer not to have external accountability. These tendencies, all the by-product of medical education and training which reward independence and self-reliance, do not serve physicians well outside of the clinic.

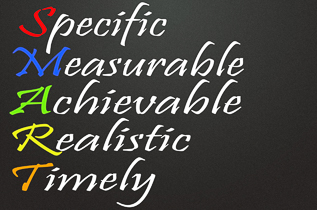

The most powerful coaching tool I use to combat both internal and external resistance during goal setting is to insist that clients create “SMART” action steps. That means writing action steps which are Specific, Measurable, Appropriate, Reasonable, and have a Timetable. Only when an action step has all five components are you likely to succeed in achieving the intended objective. As an example, you might wish to set a goal to improve your physical conditioning. An ineffective action step (an intention only) would be, “I intend to exercise more”. This is not a “SMART” action step, and is unlikely to lead to the desired result. Rewritten as a “SMART action step, it might be: I will exercise on my treadmill at a speed of 4 miles per hour and 10% inclination for 30 minutes five days a week, starting next Monday.” Note that the action is specific (treadmill walking), measurable (4 mph at 10 % inclination), appropriate (It will lead to improved physical condition), reasonable (It is within the general ability of an ordinary person), and it has a timetable for starting (next Monday). The person writing this action step is highly likely to succeed in this goal. And, because of the timetable, it is easy for a coach, friend, or family member to support the person by holding him/her accountable to do what they intend to do.

Succeeding in reaching personal and professional goals requires clear and “SMART” goals, consistent effort, asking for help when you need resources beyond your own, and someone other than yourself to hold you accountable. Use these coaching principles and next year’s New Years Resolution will most certainly come true.

Peter S. Moskowitz, M.D.

Executive Director

Center for Professional & Personal Renewal

Palo Alto

and

Clinical Professor of Radiology

Stanford University School of Medicine